In today’s installment of our blog series… Dissecting the DSM-5…What it Means for Kids and Families, we’ll take a closer look at the criteria for Specific Learning Disorder-and how the new criteria create barriers for families seeking accommodations or remedial education services for affected children.

In today’s installment of our blog series… Dissecting the DSM-5…What it Means for Kids and Families, we’ll take a closer look at the criteria for Specific Learning Disorder-and how the new criteria create barriers for families seeking accommodations or remedial education services for affected children.

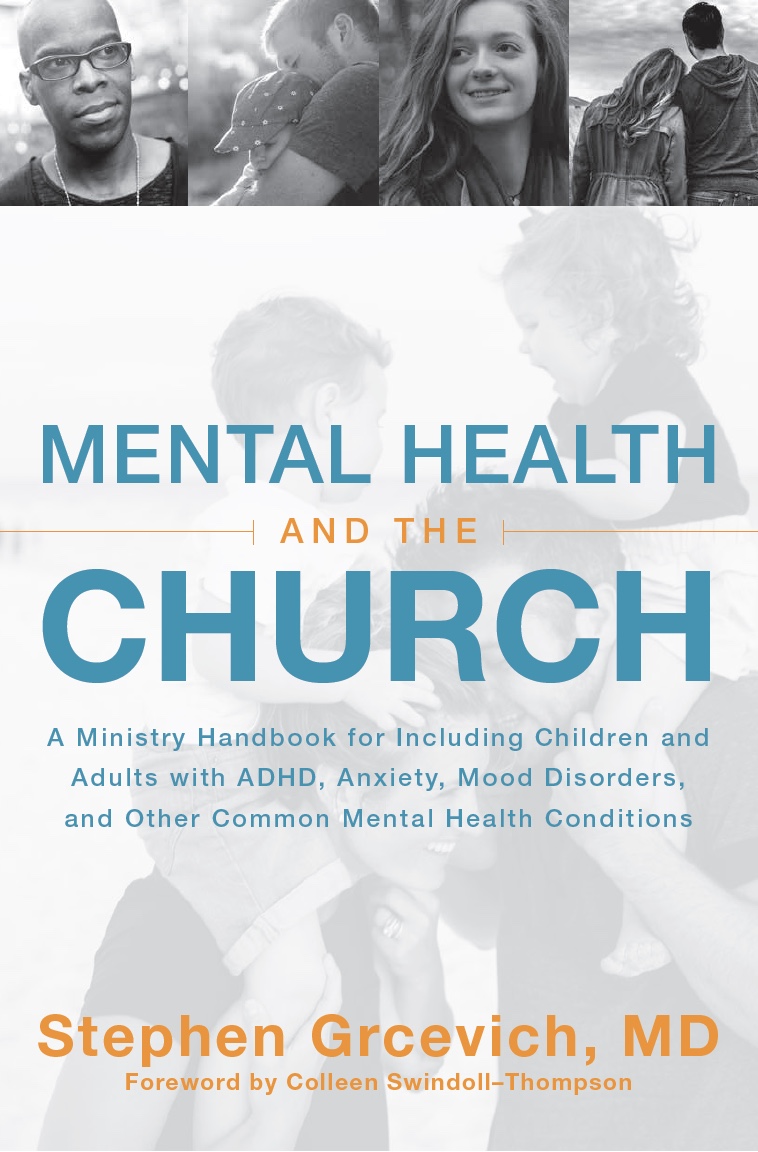

As a physician specializing in child and adolescent psychiatry, I find myself inquiring about possible (or identified) learning disabilities in nearly every new evaluation we perform. Learning disabilities are a potential cause of the academic, emotional and behavioral problems that bring kids to our practice, and are frequently a major contributor to conflicts in the home, and common comorbid conditions in kids with ADHD, anxiety or mood disorders. A thorough understanding of the impact of learning disabilities is foundational to outpatient mental health practice serving kids and families. Given the outsized role these conditions play in children’s mental health, the DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for specific learning disorder represent a major fail for the field.

The DSM-5 eliminates the categories of Reading Disorder, Mathematics Disorder, Disorder of Written Expression and Learning Disorder Not Otherwise Specified and replaces them with the term Specific Learning Disorder with specifiers for impairment in reading, mathematics and written expression, and specifiers for severity of disability.

I’ll focus my criticism on two features of the new criteria that are very problematic…the requirement that a learning disorder produce functional impairment below that expected for a child’s chronological age, and the absence of any criteria for kids and teens with learning difficulties related to weaknesses in processing speed or working memory. If you’re interested in an outstanding review of the weaknesses of the new criteria coauthored by Drs. Sally and Bennett Shaywitz of Yale’s Center for Dyslexia and Creativity, with Ruth Colker and Jo Anne Simon (from The Ohio State University School of Law and Fordham School of Law, respectively), click this link.

Among the criteria in the DSM-5 for specific learning disorder is the following…

The affected academic skills are substantially and quantifiably below those expected for the individual’s chronologic age, and cause significant interference with academic or occupational performance , or with activities of daily living, as confirmed by individually administered standardized achievement measures and comprehensive clinical assessment. For individuals age 17 and older, a documented history of impairing learning difficulties may be substituted for the standardized assessment.

The new criteria potentially pose a major impediment to families of children identified as “twice exceptional“ when defining academic achievement associated with learning disorders as “substantially and quantifiably below those expected for the individual’s chronologic age.” An important concept in the identification of learning disorders involves the use (in some states) of discrepancy measures in spotting differences between achievement (what a child has demonstrably learned) and intelligence (a measure pointing to a child’s expected level of achievement). For example, a child with measured intelligence superior to 98% of same-age peers but reading comprehension superior to 48% of same-age peers may be identified with a reading disorder (dyslexia). When Albert Einstein is referenced as a person who possibly struggled with a learning disability (admittedly, there’s no definitive evidence…he may have had ADHD, Asperger’s or a processing/retrieval issue), he likely would have qualified because of such a discrepancy, accompanied by evidence his disability produced difficulties in standardized testing.

The DSM-5 criteria would suggest that kids who markedly underachieve academically but fail to fall significantly below norms for age-matched peers shouldn’t qualify for special education intervention as a result of a specific learning disability (SLD). The updated criteria provide a rationalization for school officials to refuse additional testing or intervention when bright kids struggle but fall within the range of “normal” in academic achievement. Parents have a very difficult time fighting these determinations without trained educational advocates or legal assistance. The criteria also undermine determinations made by governmental bodies that discrepancy is sufficient to demonstrate the presence of a disability. Quoting from the Colker/Shaywitz article referenced above…

This Guidance presumes that dyslexia and other learning disabilities are readily considered “impairments” and that it should not be difficult to demonstrate that these impairments cause “substantial limitations” in major life activities such as reading that can be demonstrated on the basis of clinical evidence. In particular, this Guidance presumes the continued use of the “discrepancy” model in demonstrating the existence of dyslexia and related learning disorders. It does not require the application of specific formulae or level of severity.

I’ll share an example…Several years ago, I was seeing a boy in middle school who was prone to disruptive behavior in class. He was referred to a neuropsychologist who identified a 40 point discrepancy between his measured intelligence (99th percentile) and reading achievement (50th percentile). When placed in less stimulating classes requiring a minimal amount of reading, boredom would frequently precipitate talking out in class, impulsive speech and disrespect toward the teacher. The school steadfastly refused to provide him any remedial support to help improve his reading ability to his achievement in other areas. The end result was that the boy had been placed on medication for ADHD that did nothing to address the underlying problem and unmasked his predisposition to anxiety.

The second problem with the new standards is their failure to recognize the challenges kids experience in learning when difficulties with processing speed and working memory compromise academic performance across subject areas.

For the purpose of this discussion, working memory refers to the ability to hold new information in short-term memory and perform some mental manipulation to the information to answer a question or achieve a desired result. Working memory is important in reading, higher level thinking and achievement and is critical for planning, prioritizing and sequencing information. They may benefit from study guides that assist in identifying the most critical material to study for tests and use of multiple modalities when instructions are given. Processing speed refers to the ability to focus attention and with quickness and accuracy scan, discriminate between and sequentially order information. Measures of processing speed are sensitive to motivation, difficulty working under time pressure and well as motor coordination. Kids with processing speed delays will often experience difficulties taking in new information and generating academic products at rates commensurate with their overall intelligence. They often require copies of class notes and extended test time as educational accommodations. Weaknesses in working memory often exacerbate difficulties with processing speed and reading comprehension.

Working memory and processing speed difficulties are commonly seen in kids with ADHD…in my experience, kids with significant anxiety, OCD or an Asperger’s diagnosis are especially prone to processing speed delays. In clinical practice, these are kids who need four or five hours to complete the work that takes peers an hour or two to complete. Homework and projects become an enormous struggle. They struggle with discouragement related to school performance and medication prescribed for ADHD frequently exacerbates anxiety/obsessiveness, resulting in mood lability and irritability. The presence of demonstrable processing speed weakness accompanied by evidence the identified weakness impacts ability to take timed tests under standardized conditions is required for extended time on SAT testing. From the SAT guidelines for professionals…

Please keep in mind that a student’s documentation must demonstrate not only that he or she has a disability, but also that the student requires the accommodation being requested. Therefore, a student who requests extended time should have documentation that demonstrates difficulty taking tests under timed conditions. In most cases, the documentation should include scores from both timed and extended/untimed tests, to demonstrate any differences caused by the timed conditions.

The following tests are commonly used to measure a student’s academic skills in timed settings. Because tests are frequently developed and updated, this list is not exhaustive. There are other timed tests that may also be used. Tests must be conducted under standardized procedures.

- Nelson Denny Reading Test, with standard time and extended time measures Stanford Diagnostic Reading Test (SDRT)

- Stanford Diagnostic Math Test (SDMT)

- Woodcock-Johnson III Fluency Measures

- Test of Written Language-Third Edition (TOWL-3)

When these tests are administered under standardized conditions, and when the results are interpreted within the context of other diagnostic information, they provide useful diagnostic information about testing accommodations. A low processing speed score alone, however, usually does not indicate the need for testing accommodations. In this instance, it would be important to include documentation to support how the depressed processing speed affects the student’s overall academic abilities under timed conditions.

While an argument can be made that working memory and processing speed difficulties represent traits that contribute to other disorders (ADHD, dyslexia) and aren’t stand-alone conditions, the failure to include any specific criteria for identification of processing speed and working memory deficits in the DSM-5 contributes to ongoing misunderstanding between mental health professionals, educators and parents, represents a missed opportunity for professionals to support parents in the process of obtaining beneficial accommodations and supports in academic settings, and increases the risk for inappropriate treatment interventions. Working memory represents a significant construct in the National Institute of Mental Health’s Research Domain Criteria (RDoC) available for objective measure grounded in an increasingly well-developed understanding of the neural circuits involved. This would have been a good place to begin the process of psychiatric diagnosis grounded in demonstrable measures of neuropathology.

***********************************************************************************************************

Key Ministry offers a resource center on ADHD, including helpful links, video and a blog series on the impact of ADHD upon spiritual development in kids and teens. Check it out today and share the link with others caring for children and youth with ADHD.

Key Ministry offers a resource center on ADHD, including helpful links, video and a blog series on the impact of ADHD upon spiritual development in kids and teens. Check it out today and share the link with others caring for children and youth with ADHD.

Thank you! As a mother of a child diagnosed with dyslexia, as well as memory and processing issues, I appreciate your thoughts. Although we pretty much knew what her issues were, we sought a formal diagnosis with the understanding that early diagnosis and a history of accommodations would be necessary for her to receive the accommodation of extra time for the SAT. It appears from your article that we will also need to establish a history of how she does in both timed and un-timed testing situations. The widespread domino-like effects that you mention are very real. While I home school her, and am very thankful for that opportunity, for one year she did attend a two day a week tutorial service for home schooled students which was very much like a school setting. The feelings of anxiety and inadequacy she came to feel in that situation led us to bring her back home full-time. Trying to undo the damage we unwittingly did when we enrolled her will take many more hours than she actually spent there. I know the Lord has great plans for her and am committed to working tirelessly with her to achieve them.

LikeLike

Hi Amy,

Thanks for the kind words. The laws impacting accommodations are sufficiently complex that many professionals working with kids with learning differences don’t fully appreciate the nuances. We’re fortunate as a practice (and a ministry) to have a special educator as qualified as Katie Wetherbee to assist our families in navigating the system.

LikeLike

Pingback: Thank you @drgrcevich for:Does the DSM-5 harm b...

There is no empirical evidence that links processing speed and/or working memories issues in children with learning disabilities. Sure, there is a causal link between phonological processing and reading, but there are definitely no causal links between any of the lower order cognitive abilities and math or writing. How can they put a specifier in the DSM-5 re: processing speed/working memory, when we don’t even know if they are causally related?

LikeLike

Thank you. I think this is an excellent explanation of the problems, and describes issues I have seen constantly in practice. As poor as the DSM-IV was in many respects, it at least allowed for NOS labels, specifically Learning Disability NOS, which then would permit explanation of working memory and processing speed issues without resorting to the inappropriate ADHD diagnosis and all the baggage that comes with it.

LikeLike

We are in the midst of this issue with our 8th grade son. He has been “tested” by the district and privately. In both cases, clearly identified both working memory and processing disorders. But, our district has been fighting us for 3 years, only offering very basic 504 accommodations which don’t get to the root of his problems. He absolutely needs 1:1 support to refocus, and to help him learn the material. Unfortunately, he is not learning in the school setting and we have spent thousands of dollars to teach him at home and he has spent many, many extra hours trying to learn and feeling like a failure. The “F” here goes to the school district, the psychologists, and even apparently the “system” fir having inadequate mechanisms and codes to accurately describe my sons learning disabilities. This is a bright boy, and in the richest country in the world, it is almost immoral and certainly unethical what is happening to him. We are going fir more private testing today but I’m not very hopeful. I was told by the school test his disorder must be described “line by line” with the DSM 5. He was given what I believe is not the main problem AHD in last. Any suggestions on what the DSM 5 should say?

LikeLike

Can you provide more information about processing speed when it appears as a stand alone condition? Or is there a reference for the information that you could provide related to this quote, “The DSM-V does not consider processing speed difficulties a stand-alone condition” and fails to include any specific criteria for identification of processing speed deficits…

What should the recommendation be then if they can’t have services? Other than a low average general IQ the processing speed is the only thing that is VERY LOW. Would this student not qualify for services then, correct? How would you explain that to a parent or even in general?

LikeLike