A study published yesterday in the British medical journal The Lancet examining the effectiveness of antidepressant medication in children and teens is receiving lots of attention on the internet and is worthy of comment.

A study published yesterday in the British medical journal The Lancet examining the effectiveness of antidepressant medication in children and teens is receiving lots of attention on the internet and is worthy of comment.

A group of scientists, led by Dr. Andrea Ciprani of the University of Oxford (and funded by the Chinese government) analyzed the results of 34 randomized clinical trials of antidepressant medication used specifically to treat major depression in the pediatric population. These are not new studies, but this is a new interpretation of older results by combining many studies addressing the same issue. Here’s what they found, gently edited for lay readers…

We deemed 34 trials eligible, including 5260 participants and 14 antidepressant treatments. The quality of evidence was rated as very low in most comparisons. For efficacy, only fluoxetine was statistically significantly more effective than placebo. In terms of tolerability, fluoxetine was also better than duloxetine and imipramine. Patients given imipramine, venlafaxine, and duloxetine had more discontinuations due to adverse events than did those given placebo.

When considering the risk–benefit profile of antidepressants in the acute treatment of major depressive disorder, these drugs do not seem to offer a clear advantage for children and adolescents. Fluoxetine is probably the best option to consider when a pharmacological treatment is indicated.

Something for parents, families, pastors and other church leaders to consider when kids are suspected to have depression and in need of help is that within the professional and mental health support communities, perceptions about the effectiveness of antidepressant medication in kids is very different from the clinical reality suggested by the research literature.

The vast majority of clinical trials of antidepressant medication for the treatment of depression in children and teens have failed to demonstrate a statistically significant difference between the response to medication vs. placebo pills. We used to think that kids responded differently to antidepressants than adults because of developmental differences in the activity of neurotransmitters, such as serotonin. It turns out there’s little difference between the response of these medications in adults to what we see in kids and teens. To explore this further, allow me to introduce you to the concept of effect size.

When a pharmaceutical company submits a drug to the FDA for marketing approval, they’re required to demonstrate in two separate clinical trials that the drug is better than nothing (placebo). As a clinician, I want to know how much better than nothing the drug is for the condition I’m seeking to treat. That’s where effect size comes in.

Effect size is a measure of the magnitude of the difference between the change from baseline seen with an active treatment compared to the change from baseline seen with placebo. Without going into the formula for calculating effect size (beyond the scope of this post), we usually end up with a ratio ranging from zero to one. When an effect size is below 0.20, the benefit of the treatment to an outside observer would be essentially imperceptible. An effect size of 0.50 suggests a moderate effect. Effect sizes of 0.80 and above suggest a robust effect. For the sake of comparison, here are some examples of effect sizes of treatments for ADHD:

- Diets restricting artificial dyes and preservatives: 0.19

- Omega-3 fatty acid supplementation: 0.36

- Atomoxetine (Strattera): 0.60

- Methylphenidate-based stimulants (Concerta, Focalin): 0.80

- Amphetamine-based stimulants (Adderall, Adderall XR, Vyvanse): 0.93

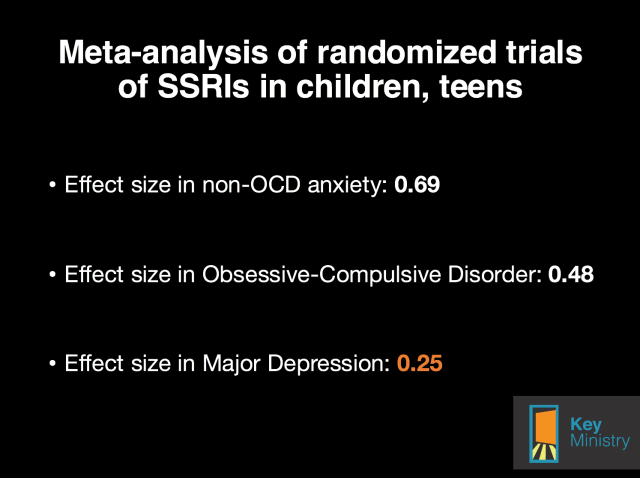

Check out the illustration below…This data is taken from an independent review commissioned by the FDA of all the placebo-controlled trials of serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and other second-generation antidepressants in children and teens. SSRIs are the most commonly used antidepressants…Prozac, Zoloft, Celexa, Lexapro, Paxil and Luvox are SSRIs:

Source: Bridge JA et al. JAMA 2007; 297(15) 1683-1696

It turns out that the antidepressants are reasonably effective anti-anxiety treatments in children and teens. SSRIs are moderately effective for Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. The effect size of SSRIs for treating depression is relatively small.

Another way of looking at this issue is by considering another statistical concept, the number needed to treat (NNT). The NNT represents the average number of patients one would need to treat to be assured a positive response was due to the effect of medication as opposed to placebo. The NNT for antidepressants in kids when used to treat depression is 10. For OCD, the NNT is 6. For other anxiety disorders, the NNT is 3.

Here’s the meta-analysis of the research literature on antidepressants in adults authored by Dr. John Ioannidis. Quoting from the paper:

The meta-analysts found 74 eligible FDA-registered trials with 12,564 patients. Among them, a third (n = 26 trials [31%] with 3449 patients) had remained unpublished. The FDA had determined that half of the registered trials (38/74) had found statistically significant benefits for the antidepressant (“positive” trials). All but one of these trials had been published in journals. Conversely, of the other half trials (36/74) that were deemed to be “negative” by the FDA, one in three were published as “negative” results; another 11 trials were published, but the results were presented in such a way so as to seem “positive” and 22 “negative” trials were silenced and never appeared in the literature.

The meta-analysts studied the estimated effectiveness of these drugs when data were combined from the FDA records and when data were combined from the published literature. For all drugs, the published literature inflated the effect sizes. The inflation varied from 11% to 69% and it was 32% on average. The FDA data would suggest that these agents had small, modest benefits (standardized effect size [ES] = 0.31 on average). Conversely, for 4 of the 12 agents, if one were to perform unawares only a meta-analysis of the published data, the summary result would suggest clinically important effectiveness (ES>0.5). This was not true for any agent based on more complete FDA data.

Here are a couple of thoughts to consider…

The professional community, parents and families hold assumptions about the effectiveness of psychotropic medication, especially medication for depression, that are unrealistic based upon our understanding of the research literature.

It’s very possible (I’d argue it’s very likely) that adults and children who respond positively to antidepressants do so not because they’re experiencing a placebo response, but because we’re treating anxiety symptoms that frequently predispose, precipitate and perpetuate feelings of depression.

***********************************************************************************************************

Key for Families has launched our first seven Facebook communities for families of kids with disabilities. We have communities for…

Key for Families has launched our first seven Facebook communities for families of kids with disabilities. We have communities for…

- Adoption and Foster Care

- Autism and Asperger’s Disorder

- Homeschooling parents

- Mental health

- Ministry families

- Parents of adult children

- PTSD and trauma

Key for Families Facebook communities are free, but registration is required. Sign up for one or more communities today, and share the invitation with friends who might want to join.

As those entrusted with the role of teacher, we need to know that essence of what we’re teaching. In other words, how would you answer this question:

As those entrusted with the role of teacher, we need to know that essence of what we’re teaching. In other words, how would you answer this question: Followers of Key Ministry, our blogs and social media platforms will notice lots of changes over the next day or two.

Followers of Key Ministry, our blogs and social media platforms will notice lots of changes over the next day or two. If you subscribe to this blog, you’ll notice a new look either tomorrow or Tuesday. If you subscribe to our

If you subscribe to this blog, you’ll notice a new look either tomorrow or Tuesday. If you subscribe to our

In February of this year, the church I attend (Bay Presbyterian Church) launched an

In February of this year, the church I attend (Bay Presbyterian Church) launched an  Recently, a staff member shared how a family with a special needs child had to change their care plan for a few weeks. Due to the change, they had to stay at home on Sunday morning for the time being. Through

Recently, a staff member shared how a family with a special needs child had to change their care plan for a few weeks. Due to the change, they had to stay at home on Sunday morning for the time being. Through  My depression greatly affects my marriage. There have been months where my husband Sergei and I have morphed into caregiver and caregivee, undesirable and painful roles we never expected to assume. And then once or if my depressive episode lifts, we begin the hard work of figuring out how to be husband and wife once again. How do we get back to loving each other? How do we love in our present circumstances regardless of mental illness? It is exhausting and painful. Sergei wrote a poem about our experience and although it cuts me until I bleed to read it, I am thankful he was able to express himself and our relationship with such poetic, truthful, and vivid terms.

My depression greatly affects my marriage. There have been months where my husband Sergei and I have morphed into caregiver and caregivee, undesirable and painful roles we never expected to assume. And then once or if my depressive episode lifts, we begin the hard work of figuring out how to be husband and wife once again. How do we get back to loving each other? How do we love in our present circumstances regardless of mental illness? It is exhausting and painful. Sergei wrote a poem about our experience and although it cuts me until I bleed to read it, I am thankful he was able to express himself and our relationship with such poetic, truthful, and vivid terms. Couples fighting mental illness often ask us what they can/should do when one spouse is depressed. Honestly, we wish we knew. We are muddling along in our marriage, at times hopeful that things are getting better and at other times feeling like the union God gave us and the life we’ve built is falling apart. So I offer these suggestions cautiously because we are no experts. We have not come out of the other side of darkness with concrete tips. But here are some things we do. And again, let me be clear, sometimes they help and sometimes they don’t.

Couples fighting mental illness often ask us what they can/should do when one spouse is depressed. Honestly, we wish we knew. We are muddling along in our marriage, at times hopeful that things are getting better and at other times feeling like the union God gave us and the life we’ve built is falling apart. So I offer these suggestions cautiously because we are no experts. We have not come out of the other side of darkness with concrete tips. But here are some things we do. And again, let me be clear, sometimes they help and sometimes they don’t. For Gillian Marchenko, “dealing with depression” means learning to accept and treat it as a physical illness. In

For Gillian Marchenko, “dealing with depression” means learning to accept and treat it as a physical illness. In

Adoption and Foster Care Community – hosted by Stephanie McKeever. Stephanie and her husband are parents of boys, one a young adult with both physical and intellectual disabilities. God is teaching her big things through her family’s trials that she probably would have never learned without them. You can find more from her through

Adoption and Foster Care Community – hosted by Stephanie McKeever. Stephanie and her husband are parents of boys, one a young adult with both physical and intellectual disabilities. God is teaching her big things through her family’s trials that she probably would have never learned without them. You can find more from her through

Homeschooling Parents of Kids With Disabilities – hosted by Jennifer Janes. Jennifer is a writer, speaker, and work-at-home mom to two daughters, ages 10 and 12 years old. She is a former public school teacher and spent a year as an artist-in-residence for the regional arts and humanities council. She is also an advocate/case manager for her younger daughter, who has multiple special needs.

Homeschooling Parents of Kids With Disabilities – hosted by Jennifer Janes. Jennifer is a writer, speaker, and work-at-home mom to two daughters, ages 10 and 12 years old. She is a former public school teacher and spent a year as an artist-in-residence for the regional arts and humanities council. She is also an advocate/case manager for her younger daughter, who has multiple special needs. Mental Health Community – co-hosted by Dr. Steve Grcevich and Julie Brooks. Julie is a nurse and tireless advocate for families impacted by mental illness. She and her husband (Todd) live in Lewisville, TX and lead a Grace Group at Fellowship Church. Their middle son (Carson) lived with chronic bipolar illness much of his life. He took his own life in July of 2010. He was 18.

Mental Health Community – co-hosted by Dr. Steve Grcevich and Julie Brooks. Julie is a nurse and tireless advocate for families impacted by mental illness. She and her husband (Todd) live in Lewisville, TX and lead a Grace Group at Fellowship Church. Their middle son (Carson) lived with chronic bipolar illness much of his life. He took his own life in July of 2010. He was 18. Ministry Families Impacted By Disability – hosted by Sandra Peoples. Prior to joining Key Ministry, Sandra served as editor of Not Alone, a collaborative website featuring authors who are raising children with special needs in the Christian faith. Her family resides outside of Houston, Texas where her husband (Lee) is planting a new church. They have two sons, one with autism.

Ministry Families Impacted By Disability – hosted by Sandra Peoples. Prior to joining Key Ministry, Sandra served as editor of Not Alone, a collaborative website featuring authors who are raising children with special needs in the Christian faith. Her family resides outside of Houston, Texas where her husband (Lee) is planting a new church. They have two sons, one with autism. Parents of Adult Children With Special Needs – hosted by Dr. Karen Crum. Karen has a doctoral degree in Public Health and Preventive Care. She promotes the health and well-being of children with autism and mental illness. She has developed and presented programs to support special-needs children, and currently focuses on educating and supporting parents as they care for their children with social, emotional or behavior challenges.

Parents of Adult Children With Special Needs – hosted by Dr. Karen Crum. Karen has a doctoral degree in Public Health and Preventive Care. She promotes the health and well-being of children with autism and mental illness. She has developed and presented programs to support special-needs children, and currently focuses on educating and supporting parents as they care for their children with social, emotional or behavior challenges. PTSD and Trauma Community -hosted by Jolene Philo. Jolene Philo is the daughter of a disabled father and the mother of a child with special needs. After 25 years as an elementary teacher, she left education in 2003 to pursue writing and speaking. She’s the author of several books about special needs parenting, caregiving, special needs ministry and her most recent book,

PTSD and Trauma Community -hosted by Jolene Philo. Jolene Philo is the daughter of a disabled father and the mother of a child with special needs. After 25 years as an elementary teacher, she left education in 2003 to pursue writing and speaking. She’s the author of several books about special needs parenting, caregiving, special needs ministry and her most recent book,

We’re delighted to announce that Beth Golik is joining our team as our new ministry coordinator.

We’re delighted to announce that Beth Golik is joining our team as our new ministry coordinator.